- Homepage

- News and Features

- 'The perfect storm' for high disease pressure

'The perfect storm' for high disease pressure

Greenkeepers across the UK are dealing with outbreaks of Microdochium patch after conditions created "the perfect storm", according to a leading expert.

The distinctive orange-brown scarring seen on putting surfaces is the result of a perfect alignment of climatic conditions that created ideal circumstances for the disease to thrive.

Microdochium Nivale, previously referred to as Fusarium, is a fungal disease that affects fine turf, particularly in mild, damp conditions. It weakens grass plants and leaves circular scars that can be unsightly while also impacting playability.

While greenkeepers are well-versed in its management, this season's outbreaks have been so severe that even the most prepared courses have been affected to some extent.

Mark Hunt, Weather Analytics at Prodata Weather Systems, said this autumn's problems were the consequence of a prolonged period of turf stress followed by a precise sequence of weather events that favoured disease.

"We've come out of an extremely dry spring and summer, and that's left many plants weakened and under stress," he said.

"When turf goes into autumn in that condition, it's more vulnerable. It's a bit like us; if you've been burning the candle at both ends, you're more likely to get ill because your body's tired. The grass plant's no different: it's been under pressure through spring and a hot, dry summer, so it's gone into the autumn slightly weaker than normal. That sets the stage."

The final trigger came with a high-pressure system that moved in during early October and trapped moisture near the surface. That weather pattern produced an extended run of heavy dew and mild overnight temperatures that gave the disease everything it needed to establish and spread.

"Normally high pressure brings settled weather, but this particular system trapped cool, moist air at ground level," Hunt explained. "That meant a lot of dew and long periods of leaf wetness, combined with mild overnight temperatures. I looked at our weather station data from the 12th to the 15th of October, and some sites recorded up to 16 hours of unbroken leaf wetness. Microdochium typically only needs about six hours to become pathogenic. Add in overnight temperatures of 11–13°C, close to its optimum growth range, and you've got the perfect storm: a wet grass leaf and mild nights."

Even consistent maintenance practices could not fully counteract the unrelenting conditions. Dew reforming throughout the day meant that even regular brushing/swishing offered only limited protection.

"Even if greenkeepers went out early to brush off dew, it would have just reformed an hour or two later and again as soon as the sun went down," Hunt said. "The plant surface stayed wet for most of the day and night, four days in a row. That's perfect for disease development, and that's why so many people suddenly saw outbreaks."

Many greenkeepers were well prepared, having applied dew dispersants and preventative fungicides in advance. However, the intensity of the conditions, coupled with the reduced potency of available chemical controls, made it impossible to fully protect every surface.

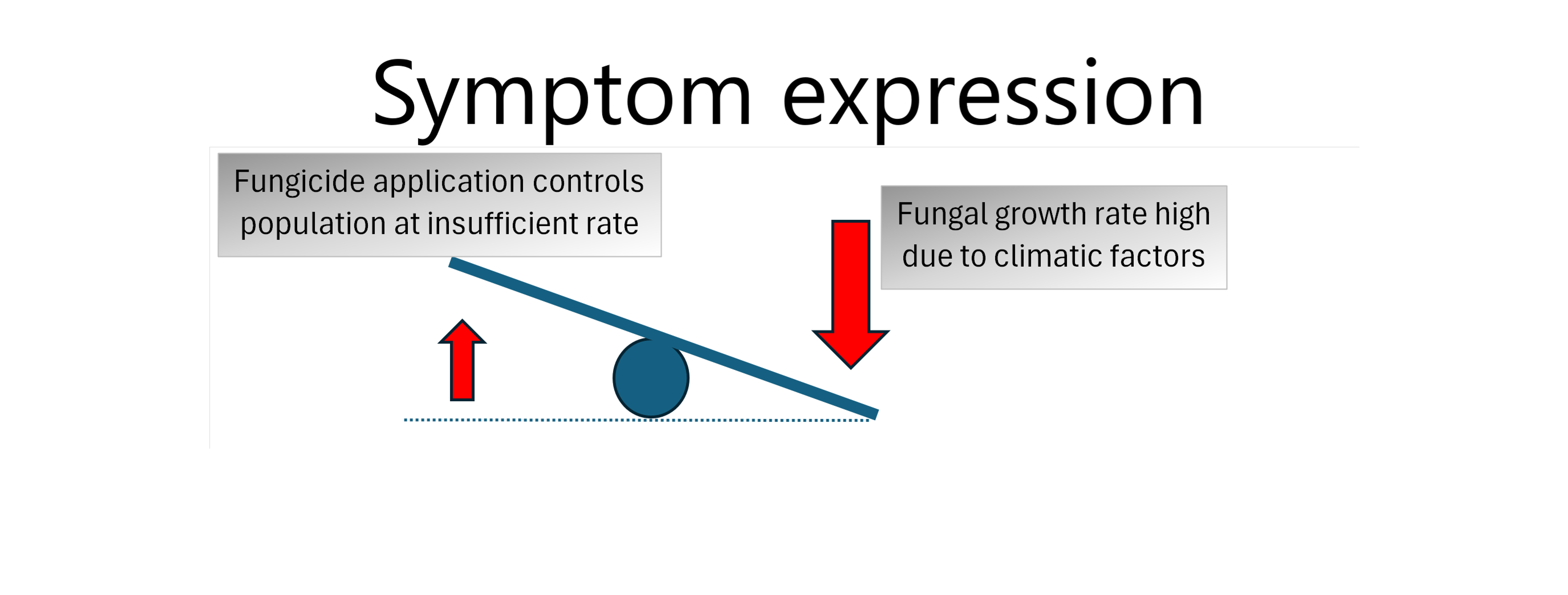

"In the past, when we had more effective fungicides, you had a good chance of containing an outbreak even when conditions were perfect for disease," said Hunt. "Nowadays, products are less effective and we must remember, they don't kill Microdochium; they slow its growth. Once infection gets going, it's very hard to stop."

Even for those who executed every cultural and chemical practice correctly, the outcome often depended on local conditions such as shade, airflow and grass species. The outbreak highlights the growing challenges posed by the changing climate, and Hunt insisted that is something everyone is going to have to come to terms with.

"The climate is changing," he said. "We're seeing warmer, more humid periods extending later into the year, conditions that favour disease development. At the same time, greenkeepers have fewer effective tools to control disease. So, you've got a combination of increased pressure from the climate and reduced chemical control – that's not an excuse; that's the reality."

That context, he believes, is vital for golfers to remember when they see diseases rear up on their courses. The problem is often not mismanagement, but an unavoidable consequence of the evolving environment and regulatory framework.

"Golfers will probably need to become a bit more tolerant to disease on their golf courses, because legislation is only going one way and the climate is only going the other," he said. "Your greenkeeper is probably working harder than ever to produce the same results, in tougher conditions and with fewer options."

Case Study 1: Whitecraigs, Glasgow

Andy Wilson, course manager at Whitecraigs, a classic parkland course on Glasgow's south side, explains the conditions facing greenkeepers this autumn and why golfers should understand that even the most proactive course teams can't always keep disease at bay

The disease pressure this year is definitely worse. We've changed the way we manage things, so we now spray preventatively when we know the weather forecast is conducive to disease conditions, and we work all year to strengthen the plant to make it more resilient. It's not easy to justify to committees, because you're spraying for something that doesn't yet exist, and it costs the best part of £1,000 each time. But it's necessary.

At this time of year, we always expect to see disease, but we try to minimise fungicide use. Even then, it can catch you out quickly. Before I went on holiday recently, I'd applied a preventative spray. A few days later, I got a call to say a couple of spots of Fusarium were showing. By the time I returned, it had spread. We sprayed again, but we'll probably have a little scarring that, hopefully, the temperatures will allow to heal before winter sets in.

Conditions in the west of Scotland are perfect for disease right now – mild, humid, and with dew forming constantly. You can take it off in the morning, and it's back within two hours.

The climate is changing, and our tools to fight disease aren't what they used to be. Products today will knock it back, but they're not as effective as those we once had.

Golfers need to understand that even the best courses will get disease. Our job is to minimise its impact, but sometimes, despite all our efforts, it's not possible to prevent.

Case study 2: Camberley Heath, Surrey

Aidan Wright, course manager at Camberley Heath, took steps to reduce turf stress and employed preventative spraying to mitigate the impact – but even his meticulous approach could only go so far

Like everyone at the moment, we've struggled with the conditions flipping on us quite quickly. We went from such a prolonged drought period, which caused so much stress on the plant throughout the back end of the season, to all of a sudden, the rain coming down, the temperature still being warm, and it just opens the door for disease to really explode.

We've looked at hitting the timing of our sprays as close to perfection as possible, but no one can get it right every time, and sometimes the weather just doesn't allow for it.

It's about keeping an eye on when you can get sprays out and maintaining the health of the plant as much as possible.

We're heavily tree-lined and have a lot of shading issues, so we do have disease on a few greens and in some bad environments, but nowhere near as bad as previously.

We lifted heights of cut early this year because last year we got hit badly. We can't take the risks anymore, so we'll go into a roll rather than a cut to avoid constantly stressing the plant, adding a few more rolls in the week when the weather allows. All these little bits help to protect us and keep conditions as good as possible for as long as possible.

Communication with members is key. As a young course manager, I've learned you need to be upfront – you are going to get disease, but if you keep people informed, it's easier to manage expectations.

We're very lucky to have a supportive board and committee, which is vital because you're already dealing with difficult circumstances and it helps a lot to have people in your corner.

BIGGA Chief Executive Jim Croxton

"Despite some very challenging climatic conditions during 2025, in general golf courses in the UK have been presented to an extremely high standard and we have seen record numbers of golfers taking advantage. A high-pressure disease period like the one we have experienced is the last thing greenkeepers want as they look to ensure golf surfaces are optimised as we move towards winter. With legislation and climatic changes continuing to make life harder for course maintenance teams, I would urge golfers and club officials to engage with their course managers to understand the challenges they face."

Tags

Author