- Homepage

- News and Features

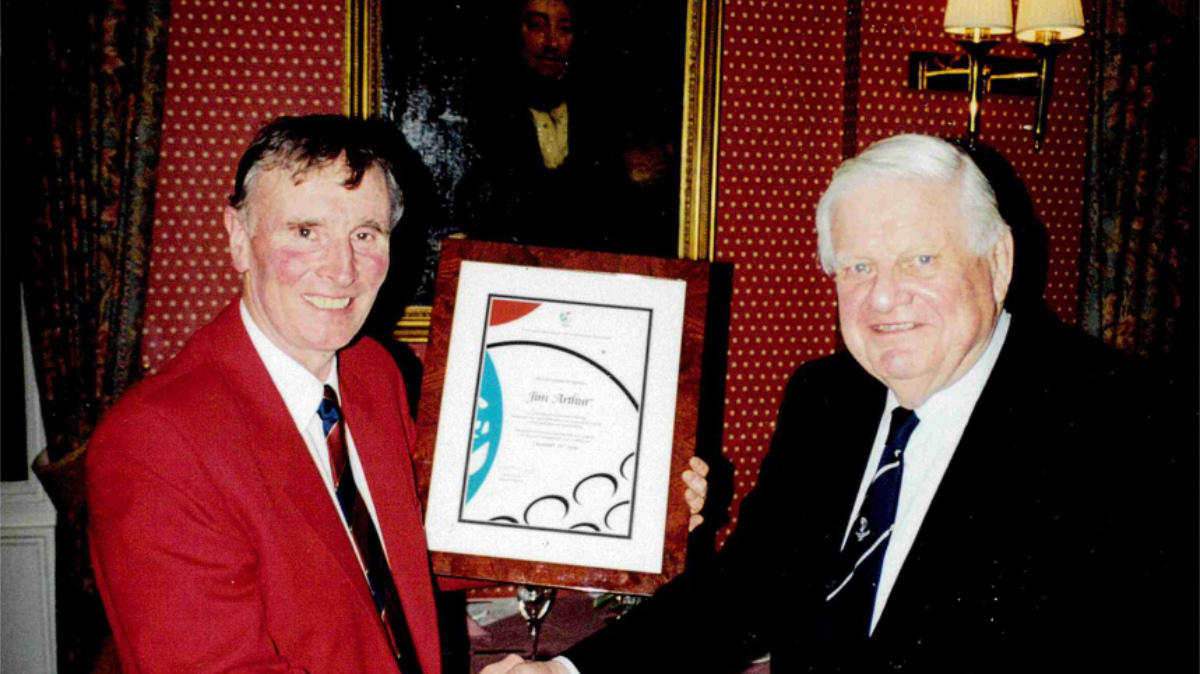

- The outspoken agronomist who 'saved' links golf

The outspoken agronomist who 'saved' links golf

In a 1996 written portrait of champion golfer Bobby Jones, the late journalist and broadcaster Alistair Cooke called it fallacy that we should “judge a man outside his time and place”, so it is with some trepidation that I attempt to do justice to Jim Arthur 100 years after his birth and 15 since his passing – are we now outside of his time and place?

Those of us in the last decade or so of our careers in turf could not be unaware of the fabled Jim Arthur, while I suspect that some in their first decade won’t have heard of him.

Perhaps the uninitiated will gain a sense of Jim from these words of his: “Essentially there is only good greenkeeping, based on encouraging bents and fescues; and bad greenkeeping, favouring … annual meadow grass.”

So, Jim’s view appeared to be black or white!

In this piece I’d like to consider what we might regard as Jim’s time and place, to try and understand from where his philosophy of turf management arose, to describe that philosophy with a bit more nuance than allowed for in his quoted statement above and reflect upon what we can make of his thinking in the context of 21st Century greenkeeping and whether he remains relevant today.

Jim Arthur was born in 1920, just two years after the end of the Great War. By 1920 golf had been played in the UK for some 563 years, whereas the USGA had been founded only 26 years earlier and no American‑born golfer had yet won The Open Championship. The USGA Green Section was founded in 1920 with the objective of providing impartial and authoritative advice for turfgrass management, although it would be another nine years before the Board of Greenkeeping Research (now STRI) was established at Bingley, West Yorkshire. It’s worth saying that although playing the same game by the same rules, golf in the UK and USA had contrasting cultural roots.

Early golf in Scotland sustained itself on the austere, windswept links, publicly accessible land that had very limited agricultural value on the east coast of Scotland, expanding onto different landscapes during the late 19th Century golf boom. The early sites for golf were often bleak places and were utilised because they provided the strategic challenges of golf and unpredictable ball behaviour that made the game interesting; they didn’t however present the visual qualities that we now often associate with golf courses.

In the United States golf was the cornerstone of the emerging country club culture; clubs which, according to Richard J. Moss, were exclusive institutions where members could display their economic and social status. In this cultural environment the golf course continued to be a playing field for sport, but also took on an ornamental function, something that hadn’t been associated with the old places for play in the UK.

As this developed, the required maintenance included irrigation to keep things green, mechanical mowers to give sharp presentation and large teams of greenkeepers to do the work. It was important that courses looked as if they were expensive to maintain – this was humankind exerting dominance over nature.

To summarise, I refer again to Alistair Cooke who, in another essay on golf, had the following to say about this difference: “Most Britons, of whatever skill, have been brought up to regard a links course as the ideal playground, on which the standard hazards of the game are the wind, bumpy treeless fairways, deep bunkers and knee‑high rough. Most Americans think of a golf course as a park with well‑cropped fairways marching, like parade grounds, between groves of trees down to velvety greens.

“Along the way there will be vistas of other woods, a decorative pond or two, some token fairway bunkers and a ring of shallow bunkers guarding greens so predictably well‑watered that they will receive a full pitch from any angle like a horseshoe thrown into a marsh.”

As a young man Jim studied agriculture at Reading University (although this was interrupted by the Second World War) and this gives us further context to Jim’s own professional development.

Jim would certainly have known about advances in agriculture in terms of mechanisation (although horses were still used until the 1960s), land improvement through extensive drainage and liming, use of selective herbicides and widespread adoption of mineral fertilisers; these methods enabling marginal land to be made productive by essentially changing the ecology.

On completing his BSc after the war Jim took up employment in the turf industry at the STRI where he found in Norman Hackett someone who helped him develop his own philosophies on turf management, namely that fine grasses produce the finest conditions for golf when nutrient status of the soils is low, particularly nitrogen, and that playability is everything.

Jim must have observed the emergence and development of golf course maintenance practices that reflected what was happening both in agriculture and on golf courses in the USA, including liming to raise pH and the overuse of mineral fertilisers and water.

He concluded that changes in ecology brought about by these practices failed to support better golf courses, given that fine turf grasses were found naturally on land of poor agricultural potential.

In Jim’s view these ‘new practices’ were so misguided as to be fundamentally wrong, because they so drastically altered the ecology of fine turf that the fine species became out‑competed by Poa annua, producing the lush and green softness described by Alistair Cooke above. The visual changes to golf courses must have been hard enough to see for such a traditionalist, but to also lose traditional golfing surfaces and with them traditional approaches to play must have left a very bitter taste for someone of Jim’s thinking.

It’s worth saying at this point that Jim was not alone in this, despite the way it might sometimes be portrayed, although he may well have been the most vocal and outspoken proponent of traditional greenkeeping. Jim describes in Practical Greenkeeping that the STRI came to promote his philosophies and the work of others including Eddie Park and his son Nick, whose thoughts on many aspects of the game are gathered in a collection of writings, ‘Real Golf’, and who were also committed promoters of all elements of traditional golf.

As the 20th Century wore on, with the hand‑in‑hand development of professional golf tours and colour TV, Jim must have felt that continuing to promote traditional greenkeeping and golfing values was like standing in front of a runaway train.

It is to his enormous credit that he didn’t capitulate over a career of half a century and left for us his Practical Greenkeeping, which so clearly sets out his philosophies as well as his approaches to maintenance.

What then were Jim’s philosophies?

Well, in the simplest way of saying it, Jim was all about working with what you have been given in terms of soils and climate (certainly in the temperate, cool‑season zones) and do all that you can to promote fine grasses.

It seems that fundamentally Jim was an ecologist, understanding that if you wanted to encourage fine grasses you had to create the conditions that allowed them to be competitive. This encompasses so much more than can be accommodated in this article, however it rests on a set of basic principles. These are described in chapter 3 of ‘Practical Greenkeeping’, and are summarised as follows:

- Aeration – “the most important operation on any course”

- Fertiliser treatment – “minimal and basically nitrogen only”

- Topdressing – “never chop and change”; “match the topdressing with the root zone”

- Mowing – “do not mow too closely to speed up playing surfaces”

- Irrigation – “the function of irrigation is to keep the grass alive”; “green is not great”

Following from these principles of course has to be the creation of policies and maintenance programmes for the long, medium, and short term. We might believe that Jim was unbending in these principles, and I think we’d be right on that, but I was surprised to learn how nuanced his approach to maintenance was: “the five laws never alter in principle, but do so very much in detail, since there are so many differing details, not only environmental, but even in the aim. No two golf courses are identical, nor indeed are the demands of golf club members, nor the aims and ambitions of course managers trying to meet those demands.” There seems to be plenty of scope within this passage for each course to find its own way (provided of course that the principles are adhered to!)

Starting this article thinking about ‘time and place’, I wonder how Jim and his philosophies regarding fine turf management look today? What is our time and place, our context, for fine turf management and do Jim’s ideas have relevance?

The ecology of fine turf grasses and other species that can co‑exist in the stressful environment of a golf green hasn’t changed in the 100 years since Jim was born and the fundamental point remains that if we want to grow fine turf species we need to create the conditions in which they can be competitive, meaning well aerated and relatively dry soils, low nutrient status, and low‑stress maintenance environments. If we can do this then bents and fescues have a chance.

We might argue that the social and technical context of golf and the tools available to us, such as modern irrigation systems, pesticides and modern fertiliser formulations, have meant that different things are now possible than they were during Jim’s career, and indeed they probably have been, for example managing turf with a reliance on preventative fungicides.

However, we also know that the context is changing and that social and environmental pressures on use of water and agrochemicals mean these tools are disappearing from our armoury.

The rational response to that has to be the development of new technologies alongside a return to methodologies that existed prior to the widespread adoption of these technologies in the 1960s and 1970s. Whatever methods we develop over the coming years, it is my view that the foundation will be on growing healthy grass, reducing stress and having less reliance on chemical interventions – these days we would describe this approach as ‘Integrated Turf Management’ – which also provides one of the foundation stones of sustainability in golf course management. The language and terminology may have changed, the fundamental biology and ecology haven’t.

In his writings Jim also commented on how little money there was in British golf when he started his career, meaning that greenkeeping teams were small and available hours had to be spent where they provided most benefit.

Over‑application of fertiliser meant more cutting, often with push‑along machines, sucking up time and money that could have been spent elsewhere. At the time of writing we are seven months into the COVID-19 pandemic, with great concern about the implications for money available to clubs and therefore the size of greenkeeping teams. Perhaps this precipitates an approach reflecting that of the 1950s – the requirement to spend hours and money as wisely as possible and, who knows, maybe less frequent mowing of areas because they’ve received less nitrogen.

It’s impossible to explore every area of Jim’s philosophies in a single article but preparing it has made me revisit his writing and re‑evaluate my attitudes to it.

Jim Arthur was clearly a man of his own time and place, however I conclude that he is also a man of ours: if we can separate Jim’s thinking and philosophy from his uncompromising communication style then we find a timeless set of principles, giving rise to nuanced, coherent, practical greenkeeping, which are all as relevant to the 21st Century context as they were when he developed them some 70 to 80 years ago.

Continue the conversation:

We’d love to hear your thoughts on the legacy of Jim Arthur’s Practical Greenkeeping. Get in touch by emailing [email protected]

Author

Dr Paul Miller

Paul has been a lecturer in Greenkeeping and Golf Course Management since 1993. Paul is qualified in the plant sciences and has previously worked in a USGA accredited soil laboratory. He is a regular presenter at Continue to Learn and contributor of articles for Greenkeeper International. He has a keen interest in golf history. Away from work Paul is an average golfer, a keen cyclist and sings in a community choir in Cupar.